Principle 1: Start with a big vision for the ultimate outcome: productively engaged adult citizen

Mentoring programs can sometimes have little, if any, impact, particularly when there is not a clear vision and specific, targeted outcomes intended for the mentoring intervention. We do not simply want to provide mentors for young people because they are lacking positive adult role models. Instead,  we provide mentors to enable them to successfully make the transition to adulthood. The ultimate goal is that young people will become productively engaged adult citizens—law-abiding, connected to meaningful work, in healthy relationships, and living in healthy environments. African American boys are likely to experience different outcomes as adults. Statistically, they face disproportionately high rates of suspension, expulsion, and drop out from high school, are more likely to go to prison than to go to college, and to father children they will not live with or parent. African American boys growing up in the child welfare system are likely to cycle in and out of the criminal justice system, to struggle with substance abuse and mental illness.

we provide mentors to enable them to successfully make the transition to adulthood. The ultimate goal is that young people will become productively engaged adult citizens—law-abiding, connected to meaningful work, in healthy relationships, and living in healthy environments. African American boys are likely to experience different outcomes as adults. Statistically, they face disproportionately high rates of suspension, expulsion, and drop out from high school, are more likely to go to prison than to go to college, and to father children they will not live with or parent. African American boys growing up in the child welfare system are likely to cycle in and out of the criminal justice system, to struggle with substance abuse and mental illness.

The research is pretty clear—when done well, mentoring can be transformative. It can inspire and guide people to pursue successful and productive futures, reaching their potential through positive relationships and utilization of community resources. It is incumbent on programs that provide mentors for youth to consider the best ways to structure their programs to maximize the likelihood that the relationship between the mentor and mentee will be transformative. Let’s consider in what ways mentoring is thought to make a difference:

In this model, Jean Rhodes (2002) is suggesting that there are certain characteristics of effective mentoring relationships—they are characterized by mutuality, trust, and empathy—and that the mentoring relationships are more likely to contribute to positive youth outcomes if the relationships contribute to social-emotional development, cognitive development, and identity development of the youth. Thus, based on this model, mentoring programs should be deliberate in recruiting and training mentors and in shaping the mentor-mentee relationship so it will make American Institutes for Research Effective Strategies for Mentoring African American Boys for a difference (i.e., through training and ongoing support of the mentors) and in guiding the mentor to address the developmental accomplishments that are critical.

Principle 2: Effective Mentoring is all about relationships, but context is also important

Meaningful mentoring relationships are characterized by mutuality, trust, and empathy. This is an important point.  Often, mentoring programs focus on matching mentors to youth based on interests or common characteristics. It is very common, for instance, for programs to have a policy that boys are always paired with adult male mentors and/or that mentors will be the same race as the youth. The evidence, however, on whether matching on the basis of race or gender in the absence of other matching criteria is equivocal on whether those relationships lead to more positive outcomes. In fact, the research shows that it is more important to consider the racial identity of the youth and the cultural competency of the mentor.

Often, mentoring programs focus on matching mentors to youth based on interests or common characteristics. It is very common, for instance, for programs to have a policy that boys are always paired with adult male mentors and/or that mentors will be the same race as the youth. The evidence, however, on whether matching on the basis of race or gender in the absence of other matching criteria is equivocal on whether those relationships lead to more positive outcomes. In fact, the research shows that it is more important to consider the racial identity of the youth and the cultural competency of the mentor.

Racial identity is a reflection of how a person has internalized their socialization experiences surrounding race. For African American boys, experiences in school while they are growing up lead to the internalization of many negative messages about boys like them — negative expectations, such as: kids like them are not usually found in advanced placement and honors courses; people like them are not found to be the heroes in the textbooks that they read; and administrators and teachers are not tolerant of the behavior of kids like them. Schools are often seen as “sites of intolerance, oppression, and dehumanization”, as is true of other social institutions and settings.

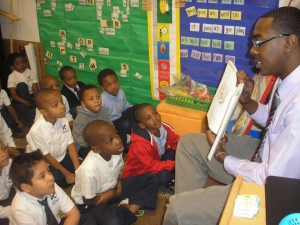

Ethnic identity is a “sense of belonging” to a cultural group which typically involves the participation in the cultural practices of that group. Research shows that when minority youth have developed a healthy ethnic identity, they are more likely to achieve more positive academic, psychological, and social outcomes. As these are the same outcomes that we hope mentoring will achieve, this finding suggests that a critical emphasis for the mentoring of minority youth is to encourage or celebrate the development of a healthy ethnic identity. In fact, a stronger ethnic identity is found more often among minority youth when they can identify a person in their life that is a role model. It is noteworthy that mentoring programs that have been shown to be particularly effective for African American boys are more likely to involve a structured curriculum that celebrates African American culture and effective roles for men within the context of such an ethnic culture.

Principle 3: Trauma experiences and exposure to violence complicate adolescent development and must be addressed

African American boys growing up in the child welfare system tend to come predominantly from a larger population of young people growing up in poverty. These youth are likely to have been raised in neighborhoods and homes where violence is prevalent. When youth experience trauma during childhood or have been exposed to serious forms of violence, there are consequences for how they accomplish normal adolescent developmental milestones. Most commonly, it will appear as if they are delayed in achieving milestones.

As adolescents, young people that have been exposed to violence and trauma (including victimization experiences) are likely to manifest certain traits. They tend to have higher rates of learning disabilities. They have difficulties with problem solving and decision making. They are more impulsive than normal adolescents and engage in a range of problem behaviors at higher than average rates. These youth also tend to struggle with interpersonal relationships and their emotional intelligence appears under-developed.

Effective strengths-based mentoring programs can build the skills of youth in each of these areas. Many of the mentoring programs highlighted in this brief provide structured group experiences that are designed to build emotional intelligence, particularly in the context of interpersonal relationships. These programs provide opportunities to practice and reflect on problem solving, decision making, and goal setting. These programs provide structured activities that occupy the time of the youth who might otherwise drift into problem behaviors. Finally, these programs create opportunities for boys to connect with men in ways that allow them to discuss common experiences around violence and trauma—a process that allows for healing and growth. The extent to which mentors can be trained in or know the features of trauma-informed care can be an asset to healing and secondary prevention.